Austro-Hungarian rule (1878–1918)

At the Congress of Berlin in 1878, the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Gyula Andrássy obtained the occupation and administration of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and he also obtained the right to station garrisons in the Sanjak of Novi Pazar, which remained under Ottoman administration. The Sanjak preserved the separation of Serbia and Montenegro, and the Austro-Hungarian garrisons there would open the way for a dash to Salonika that "would bring the western half of the Balkans under permanent Austrian influence." "High [Austro-Hungarian] military authorities desired immediate major expedition with Salonika as its objective."

On 28 September 1878 the Finance Minister, Koloman von Zell, threatened to resign if the army, backed by theArchduke Albert, were allowed to advance to Salonika. In the session of the Hungarian Parliament of 5 November 1878 the Opposition proposed that the Foreign Minister should be impeached for violating the constitution with his policy during the Near East Crisis and by the occupation of Bosnia-Herzegovina. The motion lost 179 to 95. The gravest accusations were raised by the opposition rank and file against Andrassy.

Although an Austro-Hungarian side quickly came to an agreement with Bosnians, tensions remained in certain parts of the country (particularly the south) and a mass emigration of predominantly Slavic dissidents occurred.However, a state of relative stability was reached soon enough and Austro-Hungarian authorities were able to embark on a number of social and administrative reforms which intended to make Bosnia and Herzegovina into a "model colony".

With the aim of establishing the province as a stable political model that would help dissipate rising South Slav nationalism, Habsburg rule did much to codify laws, to introduce new political practices, and to provide for modernisation. The Austro-Hungarian Empire built the three Roman Catholic churches in Sarajevo and these three churches are among only 20 Catholic churches in the state of Bosnia.

Within three years of formal occupation of Bosnia Herzegovina, Austria-Hungary, in 1881, obtained German, and more importantly, Russian, approval for the annexation of these provinces, at a time which suited Vienna. This mandate was formally ratified by the Dreikaiserbund (Three Emperor's Treaty) on 18 June of that year. Upon the accession of Czar Nicholas II, however, the Russians reneged on the agreement, asserting in 1897 the need for special scrutiny of the Bosnian Annexation issue at an unspecified future date.

External matters began to affect the Bosnian Protectorate, however, and its relationship with Austria-Hungary. A bloody coup occurred in Serbia, on 10 June 1903, which brought a radical anti-Austrian government into power in Belgrade. Also, the revolt in the Ottoman Empire in 1908, raised concerns that the Istanbul government might seek the outright return of Bosnia Herzegovina. These factors caused the Austrian-Hungarian government to seek a permanent resolution of the Bosnian question, sooner, rather than later.

On 2 July 1908, in response to the pressing of the Austrian-Hungarian claim, the Russian Imperial Foreign Minister Alexander Izvolsky offered to support the Bosnian annexation in return for Vienna's support for Russia's bid for naval access through the Dardanelles Straits into the Mediterranean. With the Russians being, at least, provisionally willing to keep their word over Bosnia Herzegovina for the first time in 11 years, Austria-Hungary waited and then published the annexation proclamation on 6 October 1908. The international furor over the annexation announcement caused Izvolsky to drop the Dardanelles Straits question, altogether, in an effort to obtain a European conference over the Bosnian Annexation. This conference never materialized and without British or French support, the Russians and their client state, Serbia, were compelled to accept the Austrian-Hungarian annexation of Bosnia Herzegovina in March 1909.

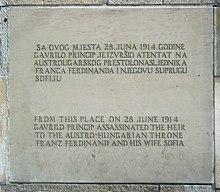

Political tensions culminated on 28 June 1914, when a Bosnian Serb nationalist youth named Gavrilo Princip, a member of the secret Serbian-supported movement, Young Bosnia, assassinated the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, in Sarajevo—an event that proved to be the spark that set off World War I. At the end of the war, the Bosniaks had lost more men per capita than any other ethnic group in the Habsburg Empire whilst serving in the Bosnian-Herzegovinian Infantry of the Austro-Hungarian Army. Nonetheless, Bosnia and Herzegovina as a whole managed to escape the conflict relatively unscathed.

The Austro-Hungarian authorities established an auxiliary militia known as theSchutzkorps with a moot role in the empire's policy of anti-Serb repression. Schutzkorps, predominantly recruited among the Muslim (Bosniak) population, were tasked with hunting down rebel Serbs (the Chetniks and Komiti) and became known for their persecution of Serbs particularly in Serb populated areas of eastern Bosnia, where they partly retaliated against Serbian Chetniks who in fall 1914 had carried out attacks against the Muslim population in the area. The proceedings of the Austro-Hungarian authorities led to around 5,500 citizens of Serb ethnicity in Bosnia and Herzegovina being arrested, and between 700 and 2,200 died in prison while 460 were executed. Around 5,200 Serb families were forcibly expelled from Bosnia and Herzegovina.